-

Search It!

-

Recent Entries

- A Little Spam Anyone?

- “Mysterious Goings On” Part Deux

- Ink & Intrigue at Ivy Tree Inn Blog Tour

- Thanks Rosie, Now it’s Time to Return Home

- Hump Day Calls Podcast

- Charlotte Readers Podcast

- First Comes Love, Then Comes Murder

- Williamsburg Book Festival February 24

- Spoken Label Podcast with Andy

- Drinking With Authors Podcast

-

Links

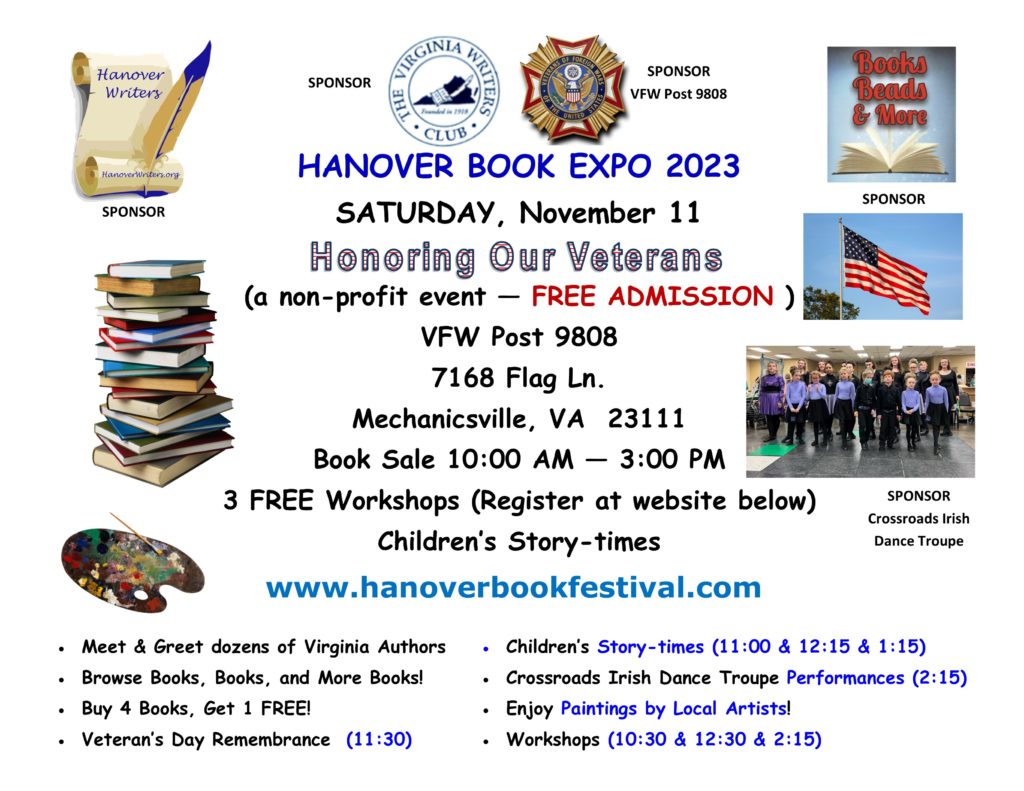

Hanover Book Festival

Comments Off on Hanover Book Festival

Posted in Uncategorized

First Chapter for Spectral Revelations

Prologue | Monday

The dumpster reeked of sulfurous rotten eggs, decomposing vegetables, and remnants of the restaurant’s catch of the day. She pinched her nose, regretting the choice of a hiding place. Peeking around the fetid trash, she watchfully awaited her mark.

He’d have to come out sooner or later.

There was a waxing gibbous moon tonight, but the scuttling dark clouds covered any sort of light it may have provided. Due to town ordinances, the limited lights in the parking lot barely spread their glow farther than five or six feet.

The flickering light he’d parked beneath flashed bright one last time and went dark. It didn’t matter; his white SUV sat like a beacon in the empty lot.

Finally, she heard the squeak of the back door swinging open.

The car beeped, and taillights blinked. He walked rapidly, carrying something in his left hand. His head swiveled back and forth, scanning the empty lot.

Silently, she pulled out of sight, going so far as to cover her mouth, even though she wasn’t close enough for him to hear her breaths. The car door closed with a quiet clunk. She waited for the telltale sounds of an engine revving to life. Instead, she heard the back door creak again and poked her head out in time to watch it close behind him.

He’d forgotten to lock the vehicle.

She pulled the sweatshirt hood over her head and darted across the lot to the SUV.

A small brown box sat on the passenger seat. In a trice, she had the box in her hands. The vehicle’s dim overhead light revealed a flash of shiny metal.

The scrape of a shoe and a skittering stone were her only warnings.

She pivoted. “Surprised to see me?”

Comments Off on First Chapter for Spectral Revelations

Posted in Uncategorized

Sunday the 15th at Elaine’s Restaurant

Comments Off on Sunday the 15th at Elaine’s Restaurant

Posted in Uncategorized

Great Escapes with Dollycas Blog Tour

SPECTRAL REVELATIONS TOUR PARTICIPANTS

SPECTRAL REVELATIONS TOUR PARTICIPANTS

October 16 – Lady Hawkeye – SPOTLIGHT WITH EXCERPT

October 17 – Christy’s Cozy Corners – CHARACTER GUEST POST

October 17 – StoreyBook Reviews – SPOTLIGHT

October 18 – Maureen’s Musings – SPOTLIGHT

October 19 – MJB Reviewers – SPOTLIGHT

October 19 – fundinmental – SPOTLIGHT

October 20 – Bigreadersite – REVIEW

October 21 – Escape With Dollycas Into A Good Book – SPOTLIGHT

October 22 – #BRVL Book Review Virginia Lee – SPOTLIGHT

October 23 – Sapphyria’s Book Reviews – SPOTLIGHT

October 24 – Mystery, Thrillers, and Suspense – AUTHOR GUEST POST

October 24 – Celticlady’s Reviews – SPOTLIGHT

October 25 – Baroness Book Trove – SPOTLIGHT

October 25 – FUONLYKNEW – SPOTLIGHT

October 26 – The Book’s the Thing – SPOTLIGHT

October 27 – Literary Gold – AUTHOR INTERVIEW

October 28 – Cassidy’s Bookshelves – SPOTLIGHT

October 29 – Cozy Up WIth Kathy – AUTHOR INTERVIEW

Comments Off on Great Escapes with Dollycas Blog Tour

Posted in Uncategorized

Murder, Mystery & Mayhem Podcast

It was a pleasure speaking the Dr. Katherine Hayes on her Podcast Murder, Mystery & Mayhem Laced with Morality. We spoke about Operation Blackbird, writing life, and what happens when we are constantly bombarded with the negativity of the News and concerns of the world today. Listen to the podcast at Spotify. Or your favorite podcast distributor.

It was a pleasure speaking the Dr. Katherine Hayes on her Podcast Murder, Mystery & Mayhem Laced with Morality. We spoke about Operation Blackbird, writing life, and what happens when we are constantly bombarded with the negativity of the News and concerns of the world today. Listen to the podcast at Spotify. Or your favorite podcast distributor.

Dr. Katherine received her BA in English and a MA in Elementary Education at Adelphi University. She received her Doctorate of Education and Supervision at Arizona State University. Katherine taught for 8 years before moving to the principalship of K-8 and K-6 schools for approximately 10 years. She has served as a freelance writer for various magazines including, Church Weekly, Prom Guide and Glendale Magazine. When Katherine isn’t working as counselor or writing curriculum she loves painting and photography. Some of her work in art, poetry and short stories has been distinguished by awards including the New York Mayor’s contribution to the arts Award, Outstanding Resident Artist of Arizona and the Foundations Awards at the Blue Ridge Mountains Christian Writers Conference. She also runs recreationally, coordinates fitness boot-camps for women and has a black belt in Taekwondo. Katherine loves speaking to groups delivering her messages with quick wit and real-life stories. She has been involved in church ministry for 18 years leading women’s ministry, teaching, playing piano, singing, and teaching liturgical dance. Learn more on Dr. Haye’s website, https://www.drkatherinehayes.com/

Arizona State University. Katherine taught for 8 years before moving to the principalship of K-8 and K-6 schools for approximately 10 years. She has served as a freelance writer for various magazines including, Church Weekly, Prom Guide and Glendale Magazine. When Katherine isn’t working as counselor or writing curriculum she loves painting and photography. Some of her work in art, poetry and short stories has been distinguished by awards including the New York Mayor’s contribution to the arts Award, Outstanding Resident Artist of Arizona and the Foundations Awards at the Blue Ridge Mountains Christian Writers Conference. She also runs recreationally, coordinates fitness boot-camps for women and has a black belt in Taekwondo. Katherine loves speaking to groups delivering her messages with quick wit and real-life stories. She has been involved in church ministry for 18 years leading women’s ministry, teaching, playing piano, singing, and teaching liturgical dance. Learn more on Dr. Haye’s website, https://www.drkatherinehayes.com/

Comments Off on Murder, Mystery & Mayhem Podcast

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged influential authors, mayhem, morality, murder, mystery, operation blackbird, podcast, writing

Mysterious Goings On Podcast

— I realized, I’ve been remiss in updating you about a great podcast I had the pleasure of being a guest on – Mysterious Goings On with Alex Greenwood. Alex is an award-winning writer, public relations consultant, speaker, and former journalist. He is best known as the author of the acclaimed John Pilate Mysteries. Every week Mysterious Goings On features interviews with bestselling authors, indies, and creative people from all walks of life.

I realized, I’ve been remiss in updating you about a great podcast I had the pleasure of being a guest on – Mysterious Goings On with Alex Greenwood. Alex is an award-winning writer, public relations consultant, speaker, and former journalist. He is best known as the author of the acclaimed John Pilate Mysteries. Every week Mysterious Goings On features interviews with bestselling authors, indies, and creative people from all walks of life.

I found Greenwood to be an excellent host ready with tantalizing and thought-provoking interview questions. For those who enjoy listening to podcasts about mysteries and creative outlets, Greenwood’s entertaining podcast is for you.

I found Greenwood to be an excellent host ready with tantalizing and thought-provoking interview questions. For those who enjoy listening to podcasts about mysteries and creative outlets, Greenwood’s entertaining podcast is for you.

You can listen to my interview with Alex Greenwood here. Intelligent Escapism and Cold War Fiction.

Join My Newsletter

Mystery Fans Unite

Enjoy exclusive content, sneak peeks, and giveaways by joining my monthly newsletter. You data will not be sold and you will recieve up to 12 newsletters a year. Click here for Newsletter sign up.

About the Karina Cardinal Mysteries

When you walk the halls of power, make sure your wits—and stilettos—are razor sharp.

An art heist, cybercrime, diamond theft, and artifact forgery. What do they all have in common? Karina Cardinal and her unchecked inquisitiveness.

As a Capitol Hill lobbyist, Karina Cardinal’s quick wit and powers of persuasion are her stock in trade. Unfortunately, her skill set includes a heaping helping of curiosity—and a talent for landing in trouble, where the crooks, conmen, and outright murderers lurk.

Lucky for her, when she finds her stilettos caught in a jam, she’s got lots of friends in the right places on speed dial. Like her intrepid colleague Rodrigo, her on-again-off-again FBI boyfriend Mike, and shadowy Silverthorne Security. Without them, Karina’s next political power suit could be a body bag. And without Karina, who’d keep her building full of nosy, quirky neighbors entertained?

Comments Off on Join My Newsletter

Posted in Uncategorized

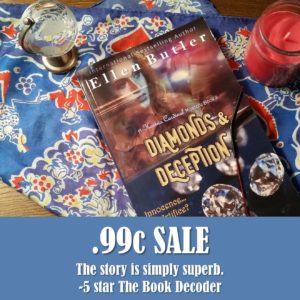

99c Sale

Diamonds & Deception on Sale Until Sunday 8-28-22

Karina’s stuck between a rock and a hard place-and these rocks are hot property.

Karina’s stuck between a rock and a hard place-and these rocks are hot property.

Sadira Manon, friend and colleague of Karina Cardinal’s sister Jillian, has been moonlighting at a jewelry store. When a loose diamond falls out of her purse, the police sing her the song of their people-“Miranda Rights.”

Karina, Jilly, and Silverthorne Security join forces to investigate who’s setting Sadira up to take a fall, and why. By the time Karina realizes they’ve dug too deep, Jillian’s in trouble, and Karina’s forced to make that dreaded phone call to Mike Finnegan, her estranged lover-hoping Mike doesn’t let it go to voice mail.

Comments Off on 99c Sale

Posted in Uncategorized

Operation Blackbird Chapter 1

Chapter One

The Recoleta

Argentina, October 1952

It was merely a glimpse, but, in that moment, memories from almost a decade ago flooded back as if it had happened only yesterday. The pungent scent of gasoline, crackling wood, and black clouds billowing in the air. Screams of terror from women and children trapped inside—only women and children, for the men had already been rounded up and marched off to a camp, the old and infirm shot on sight. Black uniforms of the SS surrounding the burning chapel. Finally, the peppering spray of gunshots, which, at that point, was merciful to those inside. I—on a ridge, too far away to do anything—watching in horror. I could smell the acrid smoke, tasting its bitterness on my tongue. The day’s hot breeze only sought to enhance the jagged memory.

The wail of a small child crying for his mother distracted me, pulling me back to the present and away from the terrible memory. The mother snatched the toddler, who was dressed in a sailor suit, by the hand and chastised him for running away from her.

When I looked back, the man had disappeared. My heartbeat slowed and the memory faded. Perhaps it wasn’t him. My vantage point was about fifteen yards away. His features had been in profile to me, and he’d been speaking to another person who had been out of my line of sight.

Of course, I followed him. Luckily, I was wearing the new pair of espadrilles I’d purchased at the market yesterday. The rope-soled shoes made little sound as I darted past the extravagant sculptures and marbled mausoleums in the Recoleta Cemetery. He’d been wearing an ocher suit, and I heard dress Oxfords tapping along the tile flag way ahead of me. At the next lane, I turned right and hurried forward, catching sight of a man’s brown shoe rounding the far corner. Barely dodging a mourner placing flowers in front of a mausoleum, I received a well-deserved frown and excused myself for disturbing her lamentations. Around the bend, I followed my quarry, only to be caught up short as I practically plowed into a bespectacled, elderly gentleman in a tan linen suit innocently reading the scripture on a particularly ornate angel statue.

“Un millón de perdones!” I gasped.

He mistook my anxiety. “Con permiso, estás perdido? Puedo ayudarle?” he asked kindly in a soft Argentinian accent.

With effort, I lightened my features. No, I assured him, I didn’t need help; I was not lost. Glancing down, I observed his brown Oxfords and realized I’d been chasing the wrong footsteps. Pardoning myself again, I retraced my path.

I put an ear out for the telltale sound of men’s dress shoes. Unfortunately, it was Sunday and the Recoleta was full of sightseeing tourists and families who had come to place flowers for their dead. Similar to the famous above-ground cemeteries of New Orleans, the Recoleta was packed tight with mausoleums, and it was easy to lose sight of someone amongst the ten- to fifteen-foot-high burial vaults. Moreover, many of the visitors had come from church and wore their best dress shoes, which clicked and tapped along the tile avenues.

After twenty minutes of traversing the labyrinth of alleyways, with not another sign of the man, I gave up and asked an elderly nun dressed in full habit if she could point me in the direction of the closest exit. Taking the map from my hand, she used her gnarled finger and drew an easy path for me to follow.

I found myself on a different road from where I’d entered at the busy main gate. A car zipped down the street, but there was little pedestrian traffic. The sun, at its zenith, beat down upon my head and shoulders, and the concrete sidewalk seemed to throw the heat back up at me. My hair prickled with sweat beneath my straw hat, and the cotton of my checked mint green-and-black dress stuck to my back. Parched and desperate for a drink, I spotted a handful of outdoor tables indicating a restaurant and headed straight for it.

Three French doors across the front of the building were open, to allow the breeze to enter. Inside, along the right, a dark walnut bar seated half a dozen diners, and tables were lined up symmetrically from front to back. The open windows, white tablecloths, walnut-paneled walls, and general hum of conversation from the patrons created an open and inviting atmosphere. I chose a small exterior bistro table, beneath a Jacaranda tree, and took the menu from beneath the salt and pepper shakers. A waitress in her mid-forties wearing a chambray dress and a yellow scarf around her neck arrived to take my order. I chose empanadas and iced tea.

The feathery leaves of the Jacaranda fluttered in the breeze, and a purple blossom dropped at my feet. I removed my hat and gently fanned myself with it. Closing my eyes, I allowed the murmur of Spanish conversations to wash over me. I’d been in Argentina for two days, and my ear was now attuned to the language.

The tea arrived, and, using the tiny tongs, I transferred the four cubes of ice from the metal cup into the warm tea along with a twist of lemon. The combined earthy-lemon flavor quenched my thirst, and I reflected upon what I’d seen.

The man must have simply borne a resemblance to the Waffen SS platoon officer who’d helped to carry out the destruction of the tiny farming town outside of Lyon, France, in 1944. The town had been destroyed in retaliation for a successful French Resistance mission which blew up a rail line and killed a dozen soldiers, including an SS-Sturmbannführer. Eighty-six people were murdered. I’d been a courier for the team that destroyed the rail line.

Perhaps he had merely been a ghostly vision conjured by my own imagination. After all, I had been roaming one of the most famous cemeteries in Buenos Aires. Why my subconscious would have conjured up such a horrible man, I had no idea.

A different waiter—a young man in his mid-twenties wearing black pants and a white shirt—placed a plate in front of me. “Su empanada, Señora.”

I thanked him and ordered another iced tea. The outer shell of the empanada had been cooked to a perfect golden color. I poked a hole in the flaky crust of the crescent-shaped meat pie to allow the steam to escape and to cool down the pie before eating it.

Laughter erupted at the bar area, drawing my attention.

My breath caught.

The fork slipped from my fingers and clattered onto the plate. The noise was overshadowed by the boisterous merriment. Now, instead of fifteen yards, the man stood only fifteen feet away—behind the bar. A shaft of sunlight clearly lit his chuckling features, and recognition instantly flooded my senses. His hair was longer and bushier—steely locks mixed with the dark curls—and ten years of age lined his features. An extra twenty pounds made his frame stockier, but not outright fat; after all, he’d been on the thin side during the war, as were we all. He’d removed the suit jacket, rolled up the sleeves of his dress shirt, and was wiping down the bar with a white rag. I supposed he would have been considered rather attractive for a middle-aged man. Knowing the atrocities he’d committed, though, I could see nothing but the monster, even when he smiled in response to a patron’s comment.

My tea arrived, brought again by the young waiter.

“Who is that man behind the bar?” I inquired in Spanish.

The waiter barely glanced over his shoulder before answering. “That is Señor Cabrera, the owner.”

“He is popular with the customers,” I remarked as another round of laughter burst forth. “Has he always owned the café?”

“No.” The young man shook his head and put a hand on his hip. “He bought it in 1946. I grew up nearby and remember it was a rubbish street café. Señor Cabrera has made many physical improvements to the place. Now it is a true restaurant. He hired a Swiss chef and expanded the menu to include European dishes, such as the schnitzel and croute au fromage . . . my favorite,” the young man said with pride. “Europeans living in Buenos Aires come often to enjoy a taste of their own food.” He placed my empty ice cup on his tray.

The boy seemed quite proud to work at the establishment, and I needed him to continue talking. “It is quite an inviting place. Is Señor Cabrera from Spain?” I peeped at the waiter from beneath my lashes, delivering a tentative smile.

Not immune to my charm, the young man reddened. “No, he grew up on a farm in Mendoza and only came to Buenos Aires in 1945.”

“I see. But he speaks other European languages?”

“Oh, yes, French and German, some English. He spent time traveling the continent . . . when he was younger,” he said with pride.

Yes, I remember just how well he spoke French as he ordered the women and children into the village chapel before his men set it ablaze.

A patron flicked his wrist at my waiter, indicating he wanted the check.

“You have other customers; I mustn’t keep you any longer.”

He bowed and retreated.

The perspiration on my neck had dried. I replaced my hat, pulling it down onto my forehead, and shifted my chair further behind the Jacaranda tree trunk, out of the bar’s line of sight.

There were a few things I knew—first, Señor Cabrera did not grow up on a farm in Mendoza, Argentina. Second, German was his first language, not the adopted Spanish which he spoke fluently. Third, his real name was Helmut von Schweiger, and he was from Reinsberg, Germany—a small farming village west of Dresden. Finally, Helmut von Schweiger looked mighty sprightly for a supposed corpse.

Comments Off on Operation Blackbird Chapter 1

Posted in Uncategorized

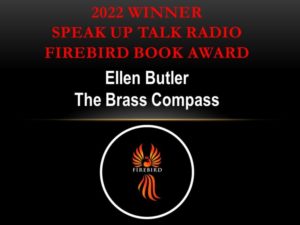

Firebird Award Winner

I am thrilled to announce The Brass Compass has won first place for the Speak Up and Talk Firebird Awards, in the Action/Adventure genre. While I’m honored to be an award winner, I submitted The Brass Compass because I value how Speak Up and Talk radio utlize the entry fees for the award.

All entry donations for the Firebird Awards help help fund Enchanted Makeovers 501(c)3 women and children’s long term shelters. The Firebird Award donation funds an ongoing pillowcase project where handmade one of a kind pillowcases, colorful totes, superhero capes, and more are sent to Enchanted Makeovers – a 501(c)(3). Each and every gift is made by hand. Entry into the Firebird book awards enables Speak Up and Talk Radio to send fun pillowcases and cheery hand sewn items to shelters around the country as a way to make someone’s life just a little bit brighter.

For purchase options and to find out more about The Brass Compass follow this link. https://wp.me/P3K9lm-9m

Comments Off on Firebird Award Winner

Posted in Uncategorized